When the Privileged Prohibit Protest

By: Kyle J. Howard Topic: Ethnic Conciliation/Reconciliation, Race RelationsMy son hurt himself yesterday. He slipped and fell and was in pain. There was no blood, there was no bruise, but his pain was obvious to everyone in the house. I picked him up, and he wrapped his arms around me. The pain the five-year-old bear felt was unbearable. This was evidenced by the tears that were coming down his cheeks. At last, he couldn’t hold it in anymore. The pain was so intense that tears alone were no longer sufficient to relieve the pain, he needed to cry out loud. It was at that point that I put my hand over his mouth and in anger fueled by inconvenience said to him, “This is not the time or place to cry out. I will let you know when it is more appropriate for you to let your pain be known…”

I know what you are thinking, I am an unloving father. If the story above were fully true, you would be right. Yes, my son hurt himself and I did pick him up. I picked him up, and I held him as he cried out. I rubbed his back and soothed him as he audibly expressed the pain. I listened to him as he told me through tears and agony that he was in pain. I asked him questions regarding where the pain was and how I could help alleviate it. I loved my son throughout the ordeal.

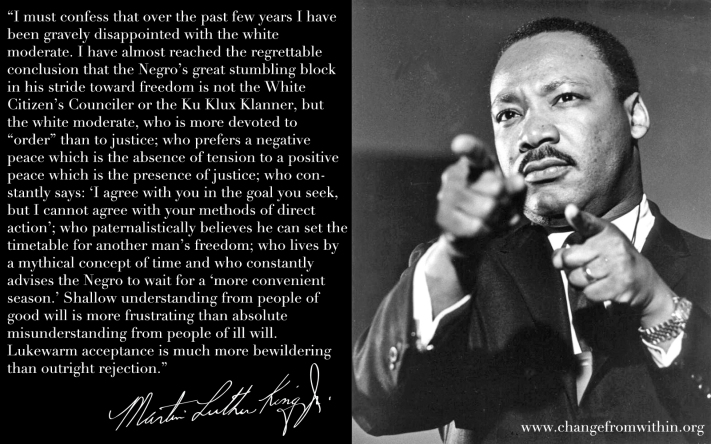

As I reflect over this past weekend, this is the scenario that comes to mind. I have witnessed, over the weekend, a multitude of people who have never experienced ethnic/racial injustice or ethnic marginalization seek to police the voice of the marginalized. This is not a new phenomenon, rather, it is one that has been part of the American reality for centuries. During the era of slavery, many white Christians were anti-abolitionists. They argued that the law would change over time and that slaves and abolitionists should be patient and wait for things to change on their own. Many of these people considered it wrong for slaves to run away from their slave masters and did all they could to return slaves to their postures of bondage. One such man was an attorney named Francis Scott Key. Francis was a slave owner who was also an anti-abolitionist. He used his legal clout to indict abolitionists as well as force runaway slaves back into lives of subjugation. However, Key is not remembered for these acts. He is mostly remembered as the author of the Star Spangled Banner, the national anthem. In the era of slavery, black people were killed for protesting. Those with power and privilege have not only policed black voices during slavery; they did the same during Jim Crow as well. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote a famous letter to white pastors known as The Letter from a Birmingham Jail. In King’s letter, he rebuked white Christians for telling him that he was divisive and an agitator for not waiting to speak out and/or protest. They argued that King was choosing a bad time and method for protesting. This was the argument of not just white pastors; the majority white evangelical population shared the same sentiment. They believed that King and others needed to wait on a “better time” and “better place”. Evangelicals were silent during the Civil Rights movement largely because they disagreed with the timing and method chosen by the black community to express their pain in action.

Today is a day that carries with it the potential for great change. Ethnic conciliation and reconciliation can make its greatest strides in this hour. However, it will require a multitude of people to look in the mirror and look at something ghastly. A reflection of themselves that exposes something that will take supernatural humility to accept; the fact that they are the white moderate who King rebuked in his letter.

Now, I am happy to admit that most of the Christians I know are not telling black people they shouldn’t protest. Many have said at one point or another that they agree that social injustice should be protested against. It isn’t the content they disagree with, but the method. Still, I believe one of the most crucial questions that such people can ask themselves is the following: Why? Why do you disagree with the method? What is it about the method you disagree with? I think that if many would ask themselves the “Why” question, an unhealthy devotion to country will be exposed. Allow me to elaborate.

The argument many will espouse is that it is unpatriotic to kneel during the National Anthem. They will argue that kneeling during an anthem is disrespectful to the sacrifice of soldiers and the American flag. This is a strange connection to me, but I also understand it. One of the issues here is that a flag is an inanimate object, and so it lacks the sentience necessary to feel disrespect or offense. Why do we personify a flag? The U.S. flag does not have emotions, and furthermore, no one has said anything about in it this conversation. Bringing up the U.S. flag in this conversation is a red herring. It has more to do with idolatry and a false narrative than reality.

I understand this reality uniquely as I too once idolized and personified a flag. As a former gang member, my flag was my life. If anyone insulted my flag, it was equal to insulting me and everything I and my group stood for. The flag we idolized was a god to us because we found our sense of identity and sense of worth in it. When we witness people, even Christians, become defensive over their country’s flag, to the point where they compromise love, it’s idolatry. For Christians, It is idolatry because they chiefly belong to the Kingdom of God whose banner is Love. To compromise love in an effort to defend the American flag is to prioritize the Kingdom of Man over the Kingdom of Heaven.

The other argument is that it is unpatriotic to kneel during the anthem because soldiers have sacrificed their lives for their country and doing so is disrespectful to their sacrifice. Respectfully, I do not understand the logic that argues that an anthem can fully embody the sacrifice and service of military personnel. In my view, it is more unpatriotic to reduce the sacrifice of a person into whether or not people stand when a song is sung, or a flag waved. I believe such a posture actually minimizes the depth of sacrifice. It is more patriotic to recognize that a song and a flag are insufficient vehicles to encapsulate the depth of a soldier’s sacrifice for their country and its ideals. Soldiers didn’t die for a song. They didn’t die for a flag. At least, I hope not. Giving your life for a song and a flag is idolatry. There was a time when I was willing to do both, though it was a different flag and it was an oath. I would like to believe that soldiers, who give their life in service, are doing so for a collective people and an ideal that transcends both a piece of cloth and words in a song.

Don’t get me wrong; I don’t think it is inherently wrong to be thankful for an anthem and flag and what they represent. My point is that we give such things too much power and authority if we measure people’s faithfulness according to how they relate to them. It is fine to be thankful for your nation’s flag. It is fine to be proud of your nation’s anthem. It is idolatry to place these things and your relation to them over and against others. This reality is intensified when one considers what the others are seeking to bring attention to, and the context and source of the anthem itself. The national anthem was written by a slave master and anti-abolitionist, and so what ideals does it truly represent? It does not represent the ideals that motivated both black and white football players to interlock their arms in unity on Sunday evening. The ideals that led to that display of unity are the ideals that propel most soldiers to give their lives for this country. Francis Key wrote a song with powerful imagery. However, his imagery is blurred by the images of his own slaves in chains. His melody is drowned out by the cries of black voices and the sounds of whips that tore their flesh from their bones. Protesting demonstrates the ideals of military sacrifice way more clearly than the lyrics and context of an anthem that contradicts justice and liberty for all. Can a song have deep meaning? Yes. Can an Anthem represent and embody the ideals of a nation? Yes, but the National Anthem that America has adopted as its own is a song soaked in hypocrisy. For many black slaves, the fact that the flag didn’t fall was their worst nightmare. It meant they would have to continue lives of slavery and bondage. It meant the promises of Freedom they were offered by the British would go unanswered. It meant that they had to continue living in a world that prided itself on the hypocrisy that justice and liberty were privileges of white men, and them alone.

Words cannot express the wicked irony that we live in today, as white men are insisting that black men stand and honor their country’s ode to white supremacy. Ignorance of this fact is understandable but not justifiable. The National Anthem, rightly understood isn’t a freedom song for black America. We live in a day where black men are accused of being unpatriotic unless they honor a song that slaps them and their heritage in the face. In my view, black Americans are some of the most patriotic members of this great republic. Why? Because they love a country that still to this day doesn’t love them. The fact that Kaepernick kneeled during the Anthem expresses real and true love. It demonstrates a love that is willing to hope the best despite consistent betrayal. Saul did not love David, he used him for his purposes and then sought his life. Kaepernick has sought to love like Hosea as he has loved and hoped in a country that has done nothing but betray him. That is patriotism in the purest form. Has this country given him wealth? Yes. But wealth for human dignity is not a faithful exchange. It is a demonic assumption to assume one should sacrifice their human dignity for a paycheck, no matter how large. I refuse to believe that soldiers have sacrificed their life for a song that was written in racist ink. I believe that soldiers have sacrificed their lives for the very ideals the black community is seeking to win for themselves. When I see coffins of soldiers being brought home, I see men who gave their life in hope that America would be better and have the chance to live up to its ideals.

Few things so clearly speak of power and privilege than for those with it to judge those without. History informs us that those in positions of power and privilege have the right to criticize the marginalized, but humility should lead them to lack the audacity. If you disagree with the practice of protest, and have never needed to protest, you should ask yourself whether you truly have the necessary filters to determine the faithfulness of marginalized people and their protests. If you disagree with the method of protest, and have never had to personally navigate the expression of collective pain, you should ask yourself whether or not you are in the place to even disagree with those who have. There comes a point when, disagreement shouldn’t even be on the table for people with privilege. If you do not know the extent of one’s pain, how can you accurately judge the appropriateness of them publicly expressing it? I could sympathize with my son because I have personally known physical pain. I know, experientially, what its like to be in a degree of physical pain that requires crying out for relief. I would never tell a man who has had his arm ripped off not to wail. I have wailed over a stubbed toe, and so even if we are surrounded by the most refined citizens of society or in a sacred context, I will not judge him for crying out in pain. Likewise, if you are white and do not know the extent and depth of black pain, you don’t even have a category for assessing whether or not a football stadium and an anthem is the proper timing to express it. Your energy should be spent on seeking to understand the pain of being black in America and not seeking to judge the appropriateness of its expression.

Black people are tired. Maybe we are too tired from the racial antagonism, indifference, and injustice to stand during the National Anthem. Maybe we are tired of trying grasp the promises of liberty and justice for all and always grasping air. Maybe our bodies are too tired from all the years of seeking to wrap ourselves in the flag that the privileged have been able to salute. The flag doesn’t represent us, but we want it to. We cry out for the right to own the flag as our own. We are tired, our energy has been spent fighting to belong, and now you criticize our weakened posture of kneeling? Maybe we could stand upright if we weren’t so tired from fighting this battle alone. Maybe we could stand during the Anthem if we were not left to fight a several century-old battle alone. But no, instead of holding us up Like Aaron did the arm of Moses, you watch us spend ourselves. You watch us be murdered and imprisoned. You watch our pain and when we cry out, instead of holding us, you tell us now isn’t the time or place. We will continue to cry out; we will continue to kneel and be held by our father in heaven. We will not wait for our brothers to wake up and become our keeper.

*It must also be said that Trump and others have successfully hijacked this whole situation to reenforce their agenda. Athlete kneeling has NOTHING to do with patriotism and this isn’t a debate about patriotism. This is about racial injustice and police abuse of power towards people of color. We must not let our President or those with similar agendas distract from the real issue at hand. This isn’t a debate about acceptable ways of protesting. This is about America holding its police officers accountable when they kill unarmed black people. Don’t lose focus on the true issue at hand no matter how hard certain people. are trying to hijack and redirect the issue.

You can follow me on Twitter @KyleJamesHoward. Also, check out my podcast “Coram Deo Podcast” which focuses on issues concerning Biblical Counseling and Practical Theology. You can search for podcast on any major podcast catcher, listen on the web here, follow updates @CoramDeoPodcast, or just click the artwork below.

Kyle J. Howard currently serves the church as a trauma informed soul care provider. Though his Soul Care ministry is comprehensive, he his primarily focused on counseling, teaching, and raising awareness about Spiritual abuse/trauma as well as racial trauma. Kyle holds an Associates in Biblical & Theological studies, a Bachelors in Christian Counseling, and is receiving his M.A in Historical Theology in a few weeks.